If you ever visit NYC, there is a little hidden

surprise when you take the six train.

A passenger can remain on the train as it turns around

in order to view a stop that has not been in operation since 1954. The old

‘City Hall’ stop is a huge hit amongst tourists, but here is the problem: the

turnaround is debatably legal. Despite many signs, blog posts, news reports and

people telling me that it is legal, a friend and I recently received tickets

for making this journey. The tickets were $50 each, and I was really upset

because it is in fact not illegal to take this journey. I fought the case in

the Transit Adjudication Bureau (TAB) court and you guessed it, I lost! This

post isn’t about whether riding the six train around the turnaround is legal or

not (since we know it is legal), but whether the cost of fighting a ticket is

worth your time and money.

Time Is Money

Let’s assume you, like me, think you are going to win

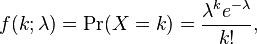

this ticket. You are so sure, that the probability of winning the ticket is I

P(Winning) = 1. Winning in this case means you do not have to pay the ticket,

so your total fine cost = 0. However, you do have to sit in the misery (and boy

do I mean misery), of the TAB offices for three hours while you dispute your

case.

So EVEN if you know you are going to win, it is still

going to cost you:

Loss

= 0 + 3*[Hourly Rate].

If you wanted your loss to be less than the cost of

your ticket, you could solve the equation and your hourly rate would need to be

less that $16 just to fight the ticket knowing you are going to win.

But what if you don’t, then how much would need to

make?

How to read this graph: it is only beneficial if your

salary is below that black line at that probability. So if you are 75% sure you

are going to win the case, your hourly rate would need to be less than $12.

If you are say 50% sure and make minimum wage, it is

not worth your time. Of course, I’m assuming you would be working from 9-3 (the

only hours of operation for TAB), and that you are using your Paid Time Off as

a factor.

In a strictly cost-benefit analysis, the cost of

fighting a ticket is rarely worth it. So if you are a rational human being,

just pay the ticket and move on. But if you want to prove a point to the system

(like I did), then go ahead and fight it. Right?

Freedom and Democracy

Will Prevail

When I fought the ticket I knew I was going to ‘lose’

money (as in time), but what is the cost of Justice and knowing that the court

system got it right? I mean sure, the colonists threw a lot of tea in the ocean

that day, but that tea represented the price of freedom and democracy, and that

really does not have a price.

The sad part is, the TAB court system was not

accepting of these ‘point-makers’ or freedom fighters. The room holds about 250

people, and it was packed. It gave me the sense that the judges do not really

care about the cases: they are simply doing their jobs. They are only safety

nets so that you don’t sue the TAB for being unconstitutional. They have this

system in place because they have to, not because they are trying to change the

world. Sadly, when you fight a ticket, you are just one person in a sea of

humans. The time within the office is very formal. Though you are attempting to

fight your case as an injustice, you are treated as if you are begging them to

not fine you.

Sometimes We Do Win

Occasionally people decide to hop over subway turnstiles

in order to avoid paying a fare. In NYC you do not need a card to exit the

system, only to enter it. Some people know that it is actually smarter to risk a

ticket than to pay the fare. The maximum ticket a TAB officer can give is $100

- normally the penalty for jumping the turnstile. The cost of a ride is $2.50,

so again the simple math is

Loss = cost*risk

100 = 2.5(#times jumping)

As long as you only get caught once every 40 times, it

is actually smarter for you to jump the gate. That means if you get caught

about once a month, it may be smarter to risk it and jump the turnstile and not

pay the MTA machine. (Can you tell I’m bitter yet?)

Why The MTA SHOULD Ticket

The MTA almost surely has a cost benefit to this: what

is the amount of tickets they can issue before the government gets involved? If

the MTA keeps their ticket processing capacity the same, but issues more

tickets, it means less people would be willing to wait longer and longer hours

at TAB just to fight a $50-$100 ticket.

Hours

to wait = #tickets*(Processing time per judge)

The processing time per judge would likely remain the

same, but if the number of tickets issued increases, so do the hours of wait

time. The graph above is based off my single sample of 3 hours, but what if

that time went up to 4 hours? That would mean even if I was 100% sure I would

win, it would only be worth my time if I made less than $12.50 per hour. So the

MTA should increase the number of tickets they issue, thus increasing the hours

to wait at TAB, and then decreasing the probability someone will fight a ticket.

This is a fine line though, because if the MTA sets

the ticket-issuing number too high, the government (hopefully) would come in

and regulate the system by enforcing a swifter trial or by making the ticketing

rules stricter and thus decreasing the number of tickets issued.

Conclusion

If you ever get a ticket, just pay it. Or at the very

least, fight the ticket and blog about it. Maybe I actually got something out

the ticket (which I’m finally going to pay). I have a story to tell at bars,

coffee shops, and most importantly, on my blog. This post is pretty cynical and

critical of the MTA, which it naturally should be. I actually don’t mind the

subway too much. Sure it smells like pee 90% of the time. It also manages to

remain 110 degrees under ground despite it only being 60 degrees outside. Sure

there are something like 113 track fires per year, but running the MTA is not

easy, so I’ll be kinder next time I take that six train around.